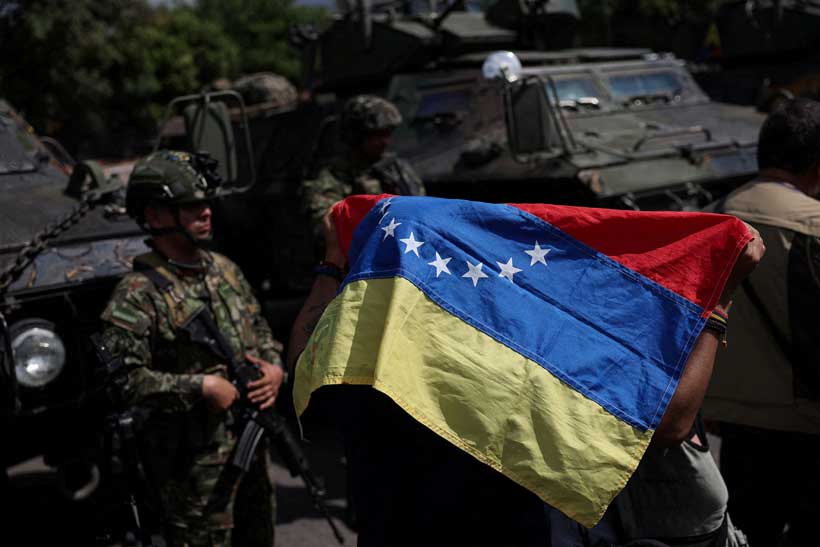

The capture of President Nicolás Maduro in January 2026 crystallised a set of dilemmas that reach far beyond Venezuela’s borders. Framed by Washington as a law-enforcement action grounded in criminal indictments, the operation also resembled an extraterritorial use of coercive power that carries profound legal, political and regional consequences. To understand those consequences, it is necessary to move beyond the immediate question of Maduro’s legitimacy or culpability and examine how law, force and precedent interact when power is unevenly distributed. At stake is not only Venezuela’s future, but the credibility of international law and the stability of an already fragile hemisphere.

At the heart of the controversy lies a fundamental legal tension. International law places strict limits on the use of force, permitting it only in cases of self-defence or when authorised collectively through the United Nations. Transforming a domestic criminal indictment into the justification for a cross-border operation blurs the line between law enforcement and interstate coercion. That blurring is not merely technical. It undermines the very logic of a rules-based system designed to protect weaker states from the discretionary exercise of power by stronger ones.

The issue becomes even more acute when prosecution follows capture. Head-of-state immunity is often misunderstood as a shield for impunity, but its primary function has been to stabilise international relations by preventing legal retaliation and diplomatic escalation. While international criminal law has progressively narrowed the space for immunity, especially for former leaders accused of the gravest crimes, the balance between accountability and reciprocity remains delicate. When a powerful state unilaterally detains and seeks to prosecute a sitting foreign president on the basis of its own domestic law, without multilateral backing, it strains that balance to breaking point. The likely result is not a strengthening of accountability, but a proliferation of legal contestation and defensive behaviour by other states.

For Latin America, these dynamics resonate deeply. The region’s political institutions have been shaped by a long history of external intervention in which legality was frequently subordinated to strategic interest. During the Cold War, elected governments were destabilised or overthrown not because they violated democratic norms, but because they challenged geopolitical or economic priorities. Guatemala in 1954, Chile in 1973, and the transnational repression coordinated through Operation Condor in the 1970s and 1980s illustrate a recurring pattern: interventions justified in the language of order produced authoritarianism, human rights violations and decades of institutional damage.

These episodes were not isolated deviations. They were embedded in doctrine, training networks and intelligence cooperation that normalised external influence over domestic political outcomes. Military assistance programmes and regional training institutions transmitted operational methods and professional cultures that were later implicated in repression. The institutional legacy of those interventions endured long after formal policy shifted, lowering the internal costs of coercion for domestic actors and weakening civilian oversight. The result was not stability, but a political environment in which violence and impunity became easier to sustain.

The seizure of a sitting Venezuelan president must therefore be read against this historical backdrop. For neighbouring states with fragile institutions, the signal is unmistakable: leadership outcomes can still be shaped externally when interests align. This perception alters political incentives. Elites may choose entrenchment over reform, calculating that loyalty and coercive capacity offer greater protection than legal accountability. Security forces may prioritise pre-emptive alignment over constitutional restraint. Opposition movements, in turn, may lose faith in domestic political struggle, believing that decisive outcomes lie abroad rather than within national institutions.

Selective enforcement of legal norms compounds these risks. The United States has consistently promoted accountability mechanisms against adversaries while insulating itself and its allies from comparable scrutiny. Its long-standing refusal to submit to the jurisdiction of international criminal courts, even as it invokes legal principles elsewhere, exposes a structural asymmetry. Law is endorsed when it disciplines others and resisted when it might constrain the self. This inconsistency weakens the moral authority of international justice and invites scepticism from regions that have historically borne the costs of intervention.

The contrast is particularly stark when viewed alongside other global conflicts. While Russia is condemned for violating international law in Ukraine, massive civilian harm in Palestine has generated far weaker enforcement mechanisms despite extensive documentation of abuses. Such disparities are not lost on the global south. When law is applied unevenly, it loses its universal character and becomes indistinguishable from power politics dressed in legal language.

Experience suggests that the practical outcomes of coercive leadership removal are rarely positive. Power vacuums emerge, institutions fragment, and criminal or armed networks expand into ungoverned spaces. External actors often prioritise short-term security objectives or access to resources over the slow work of political reconstruction. Without a credible, locally anchored transition framework, legitimacy remains elusive and instability persists. The humanitarian consequences — displacement, economic disruption and regional spillovers — are borne not by interveners, but by neighbouring societies.

Venezuela is particularly vulnerable to this trajectory. Years of institutional erosion, economic collapse and polarisation mean that the removal of a leader will not automatically transform the country into a functioning democracy. Absent a transition designed and owned by Venezuelans themselves — one grounded in verifiable electoral processes, the restructuring of coercive institutions and open oversight of strategic assets — outside involvement is far more likely to displace instability than to contain it. When external actors shape outcomes without domestic legitimacy, disorder does not disappear; it migrates.

This risk is amplified by the persistent pull of energy interests. Venezuela’s petroleum reserves have repeatedly skewed both internal decision-making and foreign policy calculations. When recovery is organised around extraction rather than institutional repair, governance becomes secondary, transparency erodes and sovereignty is gradually hollowed out, leaving the foundations of the state weaker than before. Transitions must be domestically owned.

Conclusion

The capture of Nicolás Maduro does not mark a new chapter in US foreign policy; it signals a return to an old script. Beneath the veneer of legal process lies a familiar doctrine — unilateral force, selective obedience to law and the enduring illusion that authority can be manufactured through power rather than politics. This is twentieth-century interventionism in modern dress: coups replaced by indictments, but driven by the same conviction that consent is optional and accountability applies only to othersm

Latin America has seen this movie before. The consequences are well documented: weakened institutions, polarised societies, militarised politics and long shadows of resentment. Each iteration promised stability and delivered fragility. Each claimed exceptionalism and produced precedent. The irony is that in seeking to defend the rule of law through force, the United States once again undermines the very norms it claims to uphold.

If this trajectory continues, international law will not collapse in a single dramatic rupture; it will erode quietly, hollowed out by selective application and instrumental use. The danger is not only for Venezuela, but for a global order already strained by great-power rivalry and declining trust in multilateral institutions.

History leaves little room for ambiguity. When the United States relies on coercion instead of constraint, the outcome is not the spread of law or democratic order, but the reproduction of instability, resentment and institutional decay. Power exercised without reciprocity corrodes the very rules it claims to defend.

What is unfolding around Venezuela is therefore not an exception, but a reversion — a familiar strategy repackaged in legal terminology yet driven by the same conviction that force can substitute for legitimacy. That conviction has failed repeatedly, leaving behind fractured states and weakened regional norms.

Plainly, the operation signals that access to Venezuela’s petroleum — not the restoration of stable, accountable governance — is the immediate objective. The legal rhetoric is quickly matched by moves that favour rapid control of extraction infrastructure, fast-tracked commercial access and regulatory changes that privilege outside investors over domestic rebuilding. When recovery is organised around securing fuel supplies and contractual advantage, legitimacy is sacrificed for expediency; any calm that follows is transactional, not durable. The predictable outcome is weakened sovereignty, hardened popular grievance and a brittle stability that will fracture once external priorities change.

The real danger is not confined to Caracas. Each time law is applied selectively, it becomes less credible everywhere. Each time unilateral action overrides collective restraint, the international system moves further from rules and closer to raw power. Venezuela is not an endpoint, but a warning: unless this pattern is broken, the costs will once again be paid far beyond the country at its centre.