Recently, former National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) director general Karl Kendrick Chua said that the Philippines is standing at a “critical juncture” that could determine whether the country finally attains sustained high growth or once again falls into a cycle of lost opportunities.

Speaking during a Makati Business Club briefing, Chua, who now serves as a managing director at Ayala Corp., noted that depending on the policy crafted, the results have been varied. “You have years where the critical juncture led to economic recession or depression. There are years where it led to economic growth,” he added.

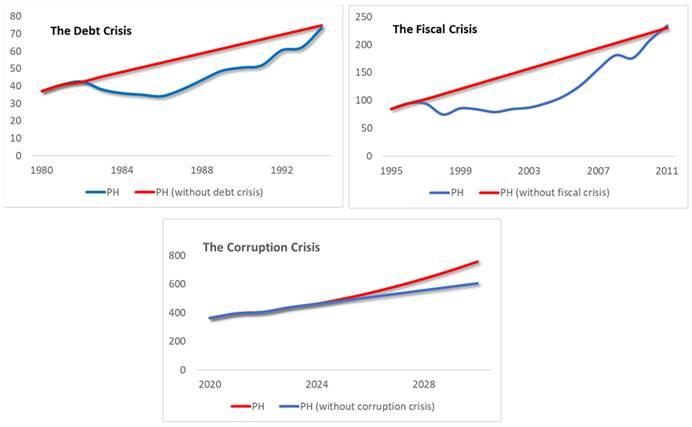

The current economic position of the Philippines is the effect of several critical junctures where policy choices either accelerated or derailed long-term development. For example, Chua noted that if the country had avoided the 1983 debt crisis and the 1997–2003 fiscal crisis, per capita income today could have matched or even exceeded Thailand’s. “These crises wiped out decades of growth,” Chua said.

To understand the magnitudes involved, it is instructive to go beyond these remarks. So, let’s take a closer look at these past losses and the more recent ones.

Debt, fiscal and corruption crises

Starting in 1983, the debt crisis penalized the Philippine GDP for a decade.

Let’s assume that the economic trends that had prevailed prior to the crisis would have prevailed without a crisis. In this view, it was only after the early 1990s, that the Philippines GDP first got to level where it had first been 10 years before. In economic terms, the debt crisis was a lost decade.

Adding the cumulative losses, it cost the economy over $152 billion.

What about the fiscal crisis?

Starting in the mid-1990s, this crisis penalized the GDP until 2011. Again, let’s assume that the economic trend that had prevailed before the fiscal crisis would have prevailed without a crisis. In this view, it was only in the early 2010s that the Philippines GDP got to the level where it had first been almost two decades before.

Adding the cumulative losses, it cost the economy over $630 billion – over four times more than the prior crisis.

Although flood-control corruption is an old challenge, the present crisis associated with it – assuming the critics are right – moved to a new level after 2022. In that case, assuming the present trends prevail, it could penalize the GDP by more than $191 billion by 2028.

Notice that in the case of the debt and fiscal crises, we have historical economic data that allows us to test counterfactuals. Whereas in the case of the flood-control corruption, we are comparing economic performances in the Duterte years (2016-2022) and in the projected Marcos Jr. years (2022-28), in order to assess the economic value of missed opportunities.

The Costs of Three Crises. GDP, current prices; in billions of U.S. dollars. Source: IMF/WEO, author

Losses of almost $1 trillion in four decades

In a current project, I am examining the economic development of most world economies from the 19th century up to 2050. The kind of losses that the Philippines has suffered are typical to conflict-prone nations, but somewhat unique in countries that should benefit from peacetime conditions.

The lost opportunities and economic value associated with these crises indicate that in the past 45 years or so, the Philippine GDP has under-performed far more often than it has engaged in more optimal growth.

That translates to missed opportunities of massive magnitude, in light of the size of the economy. All things considered, these losses could amount to more than $970 billion.

Overcoming misguided and self-interested economic policies that serve the few at the expense of the many is vital in a nation, where poverty and food security is the nightmare of every second household.

Pressing need for development and smart diplomacy

According to public surveys, the national priority issues are topped by the need to control the rise in prices of basic goods and services (48%) and fighting corruption (31%). Other major concerns are also domestic featuring affordable food (31%), improving wages (27%), and reducing poverty (23%).

These are all pressing domestic, bread-and-butter issues. And yet, although foreign policy issues represent a fraction in popular national priorities, much of the country’s policy attention and resources have been allocated to precisely such priorities.

Of course, the country should insist on its national interest, but that interest should be defined by the needs of the many, not by the priorities of the few. And that should mean focus on inflation control, corruption, food security, rising wages and poverty reduction.

Most Southeast Asian nations have elevated their economic fortunes by accelerated economic development and smart regional diplomacy. There is no reason why the Philippines couldn’t or shouldn’t do the same.

Most Filipinos would certainly agree.

*Author’s note: The original version was published by The Manila Times on November 24, 2025