Once again, Pakistan’s prime minister has stressed that `the President must continue his efforts for [the] facilitation of a peaceful solution of the Jammu and Kashmir dispute’. Besides Kashmir, there are Sir Creek and Siachen Glacier issues. These issues were almost resolved, but Indian politicians left them in limbo at last minute.

Siachen Glacier and Sir Creek: India’s former foreign secretary Shyam Saran, in his book How India Sees the World (pp. 88-93) makes startling revelations about how this issue eluded solution at last minute.. India itself created the Siachen problem. Saran reminisces, in 1970s, US maps began to show 23000 kilometers of Siachen area under Pakistan’s control. Thereupon, `Indian forces were sent to occupy the glacier in a pre-emptive strike, named Operation Meghdoot. Pakistani attempts to dislodge them did not succeed. But they did manage to occupy and fortify the lower reaches’.

He recalls how Siachen Glacier and Sir Creek agreements could not fructify for lack of political will or foot dragging. He says ‘NN Vohra, who was the defence secretary at the time, confirmed in a newspaper interview that an agreement on Siachen had been reached. At the last moment, however, a political decision was taken by the Narasimha Rao government to defer its signing to the next round of talks scheduled for January the following year. But, this did not happen…My defence of the deal became a voice in the wilderness’.

Similarly, demarcation of Sir Creek maritime boundary was unnecessarily delayed. Saran tells ` if we accepted the Pakistani alignment, with the east bank of the creek as the boundary, then Pakistan would get only 40 per cent of the triangle. If our alignment according to the Thalweg principle was accepted, Pakistan would get 60 per cent. There was a keen interest in Pakistan to follow this approach but we were unable to explore this further when the Siachen deal fell through. Pakistan was no longer interested in a stand-alone Sir Creek agreement’ (Thalweg principle places the dividing line mid-channel in the river).

Saran says, `Kautliyan template would say the options for India are sandhi, conciliation; asana, neutrality; and yana, victory through war. One could add dana, buying allegiance through gifts; and bheda, sowing discord. The option of yana, of course would be the last in today’s world’ (p. 64, ibid.). It appears that Kautliya’s last-advised option, as visualised by Shyam Saran, is India’s first option nowadays.

Kashmir dispute

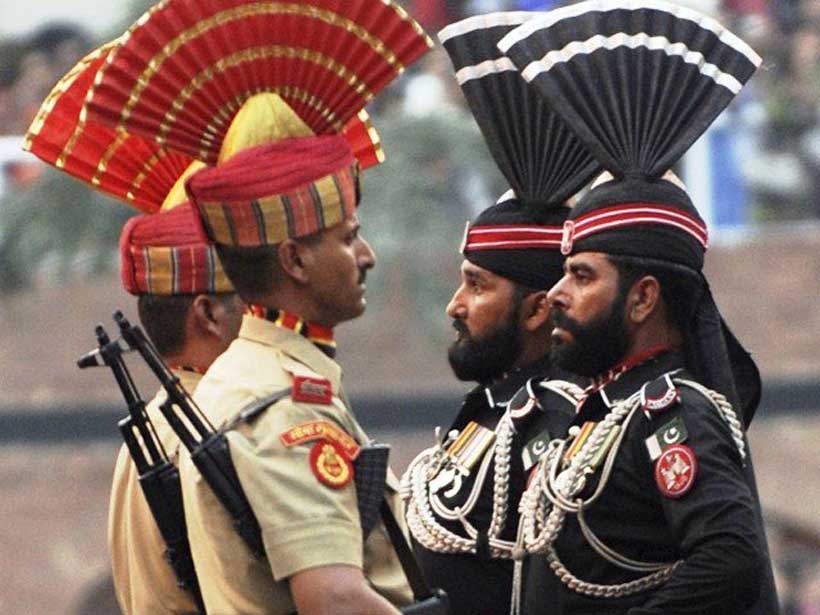

Kashmir issue has remained unresolved since creation of two independent states, India and Pakistan, in 1947. This issue led to wars between the two countries in 1948, 1965, 1971 and 1999, besides a quasi-war or military stand-off (operation parakaram) in year 2001-02. Kashmir is considered a dangerous flashpoint as both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers.

In his memoirs In the line of fire (pp.302-303), president Musharraf has proposed a personal solution of the Kashmir issue. This solution, in essence, envisions self-rule in demilitarised regions of Kashmir under a joint-management mechanism. The solution pre-supposes reciprocal flexibility.

The out-of-box Musharraf Kashmir solution is in fact a regurgitation of Mehta’s proposals. He understood that plebiscite was the real solution. But, India was not willing to talk about it. So, he says, before seeking a solution, `requirements prelusive to a solution’ should be met. He presented his ideas in his article, ‘Resolving Kashmir in the International Context of the 1990s’ (Hindustan Times editor Verghese also gave similar autonomy-inclined proposals). Some points of Mehta’s quasi-solution are: (a) Conversion of the LoC into “a soft border permitting free movement and facilitating free exchanges…” (b) Immediate demilitarisation of the LoC to a depth of five to 10 miles with agreed methods of verifying compliance. (c) Pending final settlement, there must be no continuing insistence by Pakistan “on internationalisation, and for the implementation of a parallel or statewide plebiscite to be imposed under the peacekeeping auspices of the United Nations”. (d) Final settlement of the dispute between India and Pakistan can be suspended (kept in a ‘cold freeze’) for an agreed period. (e) Conducting parallel democratic elections in both Pakistani and Indian sectors of Kashmir. (f) Restoration of an autonomous Kashmiriyat. (g) Pacification of the valley until a political solution is reached. Voracious readers may refer for detail to Robert G. Wirsing’s book India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute (1994, St Martin’s Press).

Text-books are full of solutions that could apply to the Kashmir scenario: (a) Status quo (division of Kashmir along the present Line of Control with or without some local adjustments to facilitate the local population, (b) Complete or partial autonomy of Muslim-majority tehsils of Rajauri, Poonch and Uri with Hindu-majority areas merged in India, (c) Trieste’-like solution, (d) Indus-basin-related solution (Chenab solution), (e) Aland-island-like solution, and (f) Plebiscite.

Let us look more closely at some of the tentative solutions. Status quo is now no longer a solution. It is not acceptable to any of the ‘necessary’ parties (particularly Kashmiris) to the dispute. This solution had envisaged a boundary that followed peaks of Pir Panjal Range in northern Jammu and included districts of Riasi, Kotli, and Poonch in Pakistan. India was to control Riasi and parts of the other two districts. Riasi was to include the middle reach of Chenab River, vital to Pakistan. Indian foreign minister Swaran Singh offered to cede to Azad Kashmir and the Northern Area additional 3,000 square miles of territory from India-controlled Kashmir. However, the negotiations between India and Pakistan remained inconclusive. As for autonomy proposal, it suggested that both, India and Pakistan, should grant independence to disputed areas under their control and let Kashmir emerge as a neutral country. The Trieste’-type solution, as agreed between Italy and Yugoslavia after the World War II, partitioned the territory around the port of Trieste’. The Security Council’s resolutions guaranteed demilitarisation of the free city of Trieste’. The citizens of Trieste’ enjoyed unhindered access to neighbouring Yugoslavia and Italy. Applied to Kashmir situation, the Trieste solution meant division of the Kashmir state on communal lines. Under this solution, the Hindu majority areas of Jammu and the Buddhist-dominated region of Ladakh would join India. The Northern and the Kashmir Valley (under India’s control), along with Azad Kashmir, would join Pakistan. Free access would be given to people living on both sides of Kashmir. In historical context, the short-lived Trieste’ solution is considered an ineffective solution. To India, autonomy as well as joint control, also, is Utopian solutions.

Some writers have suggested an Indus-Basin-based solution: The Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab Rivers, along with their basins, would join Pakistan. The Sutlej, Ravi, and Beas Rivers and their basins, as well as the remaining parts of Kashmir, would join India. The basin of the Jhelum would fall within the exclusive domain of Pakistan. Aland’s international accord settled the territorial dispute between Finland and Sweden. The problem got solved as Finland was sincere, unlike India. When the dispute with Sweden arose after the First World War, Finland’s Parliament passed an autonomy law on May 6, 1920 for Aland. Two other autonomy laws were passed on December 28, 1951 and August 16, 1991 to give greater autonomy to Aland, allow it to use its own flag and coat of arms, and appoint governors. On December 31, 1994, Aland joined the European Union voluntarily.

The South -Tyrol agreement between Australia and Italy provided an autonomy framework (vouchsafed by Paris Peace Agreement 1946). The framework accommodated aspirations of ethnic inhabitants of the region.

Now, a few words about the United Nations’ solution. There are fifteen United Nations resolutions guaranteeing right of self-determination to the Kashmiris. Despite its best efforts, India has not yet been able to get the ‘India-Pakistan Question’ deleted from the UN agenda. The UN observers are still posted along the two sides of the Line of Control.

The inhabitants of the state of Kashmir would themselves decide to accede to India or Pakistan (UNCIP Resolution1949). India’s attitude negates the cardinal principles in inter-state relations, that is, pacta sunt servanda `treaties are to be observed’ and are binding upon signatories. Sir Owen Dixon’s plebiscite’s proposal is the best solution, preceded by demilitarisation and self-governance. Demilitarisation of Kashmir has been the basis of United Nations Security Council resolutions on Kashmir. The UN Security Council stipulated 30 days’ period for India and Pakistan to agree on demilitarisation. This deadline was incorporated in UN Security Council Resolution No 98 of 23 December 1952. The resolution called upon India to reduce its troops in Kashmir to a range between 12,000 to18, 000. Pakistan was required to reduce her troops to between 3000-6000. History tells that the demilitarisation, and, by corollary, plebiscite, could not be held in Kashmir because of India’s obduracy. India kept insisting upon keeping a minimum of 21,000 troops. India, currently, has over seven lac troops in the occupied Kashmir. The demilitarization proposals were based on General McNaughton’s and Australian prime minister, Robert Gordon Menzes’ proposals (Korbel, Danger in Kashmir, pp.159, 168, 176-177 and186).

India’s successive defence minister ruled out demilitarisation . India’s home minister told India’s house of peoples (lok sabha) that ‘there is no question of withdrawal of forces and certainly no question of demilitarization’. Former prime minister Manmohan Singh also considered the existing LOC as sacrosanct.

Then there is Ireland’s Good Friday Agreement of 1998 model to Kashmir situation. The agreement had five main constitutional provisions. First, Northern Ireland’s future constitutional status was to be in the hands of its citizens. Secondly, if the people of Ireland, north and south, wanted a united Ireland, they could have one by voting for it. Thirdly, Northern Ireland’s current constitutional position would remain within the United Kingdom. Fourthly, Northern Ireland’s citizens would have the right to “identify themselves and be accepted as Irish or British, or both.” Fifthly, the Irish state would drop its territorial claim on Northern Ireland and instead define the Irish nation in terms of people rather than land. The consent principle would be built into the Irish constitution. The Andorra model also offers food for thought.

Andorra, is a small principality in the Pyrenees whose heads of state are the President of France and the Bishop of Urgell, called the Coprinceps. Andorra has its own government and constitution and freedom in most internal matters; in external relations the Coprinceps play a major role. The ideal is that while the status quo on the other regions can be maintained (the Northern Region with Pakistan, Jammu and Ladakh with India), in the Valley, whose overwhelmingly Muslim population have for long been agitating against Indian rule, the Andorra model can be applied. This means India would retain some control, jointly with Pakistan, over matters of defence and external affairs, but in internal and cultural matters, the Valley would be more or less completely autonomous.

Ibarretxe Proposal for the Basque conflict in Spain also offers insights. The Basque agreement is supported by three basic premises:(a) The Basques are a People with their own identity; (b) they have the right to decide their own future; and (c) it is based on respect for the decisions of the inhabitants of the different legal political spheres in which they are situated.

At present, the Basque people are organised in three legal-administrative communities. On the one hand are the Basque Autonomous Community, composed of the provinces of Alava, Bizkaia and Gipuzkoa, and the Province of Navarre, both of which are situated within the Spanish state. On the other are the territories of Iparralde (Lapurdi, Zuberoa and Benafarroa) situated within the French state that do not have their own political administration.

Another creative example is the Sami Parliamentary Assembly, established in 2000, as a joint forum of the parliaments of the Sami indigenous people who reside in the northern regions of Norway, Sweden and Finland. The Sami have been demanding greater control over the land, water and natural resources of their ancient homeland. They elect representatives to their own regional parliaments but are now trying to develop a pan-Sami political institution to better protect their rights. The three Nordic countries have all been pulled up by the UN for their treatment of the Sami and many issues—such as Norway’s decision to allow expanded bombing ranges for NATO warplanes—affect the indigenous population cutting across sovereign state borders. The Sami example is a case of an attempt by a partitioned people to craft meaningful political institutions from below, often in the face of indifference from above.

New Caledonia Model Noumea Agreement has fine advice for disputed Kashmir. In 1774, the island was discovered by English captain James Cook. In 1853, under Napoleon III, France officially took its possession. The 1999 Noumea agreement on New Caledonia, where the indigenous Kanaks are now outnumbered by the descendants of European settlers and by other non-Melanesians, maintains French nationality over the colonial possession while establishing the idea of New Caledonia citizenship over a 20-year transition period till a referendum on final status. This example is unappealing in the South Asian context because Kashmir is not a colonial possession. Nevertheless, the notion of shared sovereignty is an interesting one.

Inference: Given sincerity, there is nothing intractable about the Kashmir issue (Dawn December 31, 2017). It is a simple problem involving right of self-determination. An independent Kashmir, as a neutral country, was the favourite choice of Sheikh Abdullah and from the early 1950s to the beginning of the crisis in 1989.“Sheikh Abdullah supported ‘safeguarding of autonomy’ to the fullest possible extent” (Report of the State Autonomy Committee, Jammu, p. 41). Abdullah irked Nehru so much that he had to put Abdullah behind the bars. Bhabani Sen Gupta and Prem Shankar Jha assert that “if New Delhi sincerely wishes to break the deadlock in Kashmir, it has no other alternative except to accept and implement what is being termed as an ‘Autonomy Plus, Independence Minus’ formula, or to grant autonomy to the state to the point where it is indistinguishable from independence”. (Shri Prakash and Ghulam Mohammad Shah (ed.), Towards understanding the Kashmir crisis, p.226).

India should heed advice by its own two foreign secretary J.N. Dixit. He says it is no use splitting legal hair. “Everybody who has a sense of history knows that legality only has relevance up to the threshold of transcending political realities. And especially in inter-state relations… so to quibble about points of law and hope that by proving a legal point you can reverse the process of history is living in a somewhat contrived utopia. It won’t work.” This is a quote from V Schofield’s Kashmir in the Crossfire. Let India begin to talk.

True, honesty, not legal rigmarole will solve the Kashmir tangle.

Sans sincerity, the only Kashmir solution is a nuclear Armageddon. Or, perhaps divine intervention.