The cost of reskilling the 1.4 million US workers likely to lose their jobs as a result of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and other structural changes over the next decade will largely fall on the government, with the private sector only able to profitably absorb reskilling for 25% of at-risk workers. This is the finding of a World Economic Forum report published today.

The report, “Towards a Reskilling Revolution: Industry-Led Action for the Future of Work”, finds that it will be possible to transition 95% of at-risk workers into positions that have similar skills and higher wages. The cost of this reskilling operation would be approximately $34 billion.

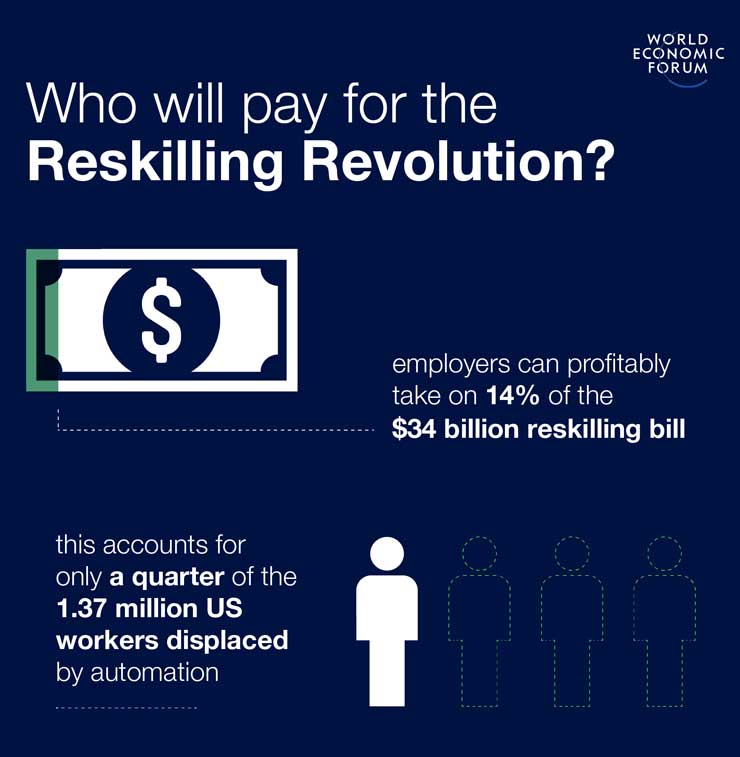

However, the report also finds that, of the 1.4 million workers at risk, the private-sector could only profitably reskill 25%, or about 350, 000 workers. For the rest, at current rates of reskilling time and costs and foregone productivity, it would be more cost-effective for businesses to replace them with workers with the correct skill-set.

The ability of the private sector to profitably absorb the reskilling burden could rise to 45% of at-risk workers if businesses collaborate to create economies of scale. The report also finds that the government could reskill as many as 77% of all at-risk workers, with a clear return on investment coming from increased tax returns and lower social costs such as unemployment compensation. For the remaining 18%, the costs outweigh the economic returns to government, while for 5% a similar-skills and higher-wage pathway is not available.

With 18% of all at-risk workers – 252,000 people – unable to be profitably reskilled by either business or the public sector, the report’s findings imply that governments must consider expanding welfare and social support, paying for negative-return reskilling due to its societal returns, and lowering the costs of reskilling and retraining through incentives to and collaboration with the private sector and educators, including apprenticeships and online learning.

The question of who pays for reskilling as hundreds of thousands of jobs become displaced over the next decade as a result of Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies – such as artificial intelligence and big data analytics – and other structural factors, is increasingly important. In a 2018 report entitled The Future of Jobs 2018, the World Economic Forum calculated that, while 75 million will be displaced worldwide through automation between 2018 and 2022, as many as 133 million new roles could be created. However, this assumes that it will be possible to provide workers with the skills to fulfil these new roles, highlighting the need for reskilling at-risk workers as well as ongoing upskilling for the majority of workers.

“Even with a conservative estimate, the reskilling challenge will cost $34 billion in the United States alone and only a part of it will be profitable for companies to take on by themselves, even if they were to think long term. The question of who pays for the stranded workers and for the upskilling needed across economies is becoming urgent. In our view, a combination of three investment options needs to be applied: companies working with each other to lower costs; governments and taxpayers taking on the cost as an important societal investment; and governments and business working together. This week at the Annual Meeting, we are exploring and building coalitions around all three,” said Saadia Zahidi, Managing Director, World Economic Forum, and Head, Centre for the New Economy and Society.

“Towards a Reskilling Revolution: Industry-Led Action for the Future of Work” is published in collaboration with the Boston Consulting Group and Burning Glass Technologies.

From planning to delivering skills

Separately, the Forum’s Closing the Skills Gap 2020 coalition, launched in 2017 with a target to reskill or upskill 10 million workers by 2020, has already secured pledges for training more than 17 million people globally. Of these, 6.4 million people have already been retrained. The initiative uses a virtual hub to capture measurable commitments from leading companies to train, reskill and upskill workers. The hub also serves as a repository of best practices and case studies.

Additionally, over the last quarter five industries began to explore the viability of making their reskilling and upskilling efforts more efficient and impactful. At the Annual Meeting, they are expected to launch sector-level collaborations to help prepare their workforces for the future of work.

To complement this business-led approach, the Forum is initiating and expanding national public-private collaboration task forces to prepare countries for the future of work. This approach has been rolled out in four economies, including Argentina, India, Oman and South Africa, with the goal to expand geographically to 10 economies by the end of 2020.

To accelerate the integration of more women into the labour force, particularly in the high-growth sectors of the future, the Forum’s Closing the Gender Gap national public-private collaborations are expanding their coverage to eight countries, including Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, France, Panama and Peru.

A long-term vision for skills

While reskilling and upskilling are critical short-term needs, the current mismatch between education and employment is the result of a system in which proxies for skills rather than skills themselves are taught, recruited, promoted and rewarded. Proxies such as the brand names of educational institutions and employers replace tangible evaluations of the quality of the skills held by employees. This system is not viable in an era of rapid labour market transformations brought on by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. It is under further pressure from social inequalities, which tend to become locked-in for those lacking the highest-value proxies for skills.

A new study, “Strategies for the New Economy: Skills as the Currency of the Labour Market”, published in collaboration with Willis Towers Watson, suggests how a skills-based system may be created through changes in the learning ecosystem, the workforce ecosystem and the broader enabling environment. It covers 10 strategies, including building, adapting and certifying foundational, advanced skills and adult workforce skills; realizing the potential of educational technology and personalized learning; mapping the skills content of jobs and developing a common taxonomy; and designing portable certifications. Such actions would have a positive impact on both labour market efficiency and socio-economic mobility.

The view from the C-suite

“Companies need to start to prepare for the future of work now, and up- and reskilling will be the biggest challenge in this endeavour. The good news is that there is a positive business case for up- and reskilling for many disrupted workers from a company and government perspective,” said Rich Lesser, Global Chief Executive Officer, Boston Consulting Group, USA.

“The shift to a skills-based economy presents individuals with the chance to compete for employment based on what they can do for a company. At the same time it gives companies a tremendous opportunity to more efficiently design work and organize resources,” said John J Haley, Chief Executive Officer, Willis Towers Watson, USA